Taking Direct Action

The Rise of the Clamshell Alliance

In 1976, New Hampshire residents took direct action against the construction of a twin-reactor nuclear power plant in the coastal town of Seabrook. For years they had witnessed how the regulatory process was stacked in favor of the nuclear industry. How could they believe otherwise? Federal regulators had never denied a permit for building a nuclear power plant.

Resistance to the project wasn’t new. Almost from the time it was proposed in 1969, there were organizations challenging it, especially the Seacoast Anti-Pollution League, the New England Coalition Against Nuclear Pollution, and the Granite State Alliance.

There also were individuals such as “Earthquake Dolly” Weinhold of Hampton, NH, who intervened in the licensing process with information about an earthquake fault near the site; Renny Cushing, also of Hampton, who repeatedly testified before the licensing board; and Ron Rieck, who, in January, 1976, became the first Seabrook occupier when he sat in protest of the project on top of a weather tower at the site for 36 cold hours.

In the early spring of 1976, residents of several coastal towns, including Seabrook, voted at their annual town meetings to reject construction of the nuclear plant. They worried that the plant threatened the fragile coastal environment, including clam flats and fisheries. Some worried that the utility spearheading the nuclear proposal – Public Service Company of NH (PSCo)—was too small and would collapse under the burden of such a monstrously expensive project. Eventually, it did.

But New Hampshire’s long tradition of “home rule” was ignored by the company and the state, which declared that the project must go forward. And when the Atomic Safety and Licensing Board approved the construction permit June 29, 1976, some New Hampshire citizens resolved it was time to take direct action.

They included people who had been involved in the civil rights, anti-Vietnam War, feminist, union, and environmental movements, and brought insights from that work, including political analysis, to their anti-nuclear organizing. They also welcomed the involvement of direct-action, anti-nuclear activists from western Massachusetts, and the example of collective anti-nuclear civil disobedience in Wyhl, West Germany.

In mid-July, they invited Sukie Rice and Elizabeth Boardman of the American Friends Service Committee to instruct them in tactics of non-violence because they had no desire to engage in physical conflict with police, construction workers, or members of the public. Quite the contrary, these citizens consciously adopted a strategy of trying to inform and persuade everyone they encountered – including police and company officials – about the dangers of nuclear power. This was rooted in a deep belief that every human being deserves respect.

On July 18, 1976, these activists proclaimed themselves to be a new organization with the intention to physically occupy the Seabrook site to prevent construction. In solidarity with the local marine life and the workers who made their living from fishing and clamming, these anti-nuclear activists called the new organization the Clamshell Alliance. Perhaps inevitably, they soon began referring to themselves individually as Clams. They declared their opposition not just to the Seabrook plant, but to all nuclear plants.

In its founding statement, the Clamshell Alliance asserted the right of citizens to “decide the nature and destiny of their own communities.” As an act of solidarity with the Seacoast community, Clamshell made a conscious decision to limit its first civil disobedience action to New Hampshire residents.

But the Clamshell always intended to be a loose alliance of New England anti-nuclear and environmental groups – some of which already existed, such as the Upper Valley Energy Coalition, Central Massachusetts Citizens Against Nuclear Power, Hampshire and Franklin County alternative energy coalitions, and other groups around New England that were born in 1976. These organizations formed affinity groups to send to Seabrook occupations, but they also were active in their own areas, educating people, holding rallies, and gathering support.

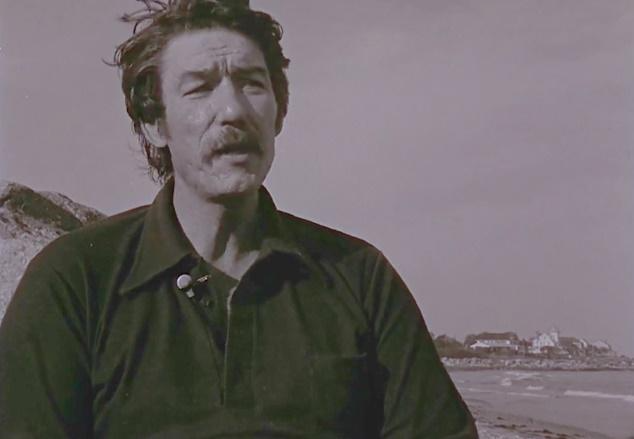

The Clamshell Alliance resolved to increase its numbers 10-fold with each subsequent action. Guy Chichester, a 41-year-old carpenter who was one of the original founders, told a public meeting in Lebanon, NH, July 25, 1976: “If they arrest 20, we’ll come back with 200. If they arrest 200, we’ll come back with 2,000.”

August 1, 1976 (The Last Resort, Green Mountain Post Films)

Occupations of the site were the prime focus of the Clamshell. But care also was taken to respect legal protest and recognize the issues were much bigger than just nuclear power. That’s why occupations usually were preceded by a legal public rally, where guest speakers included renewable energy advocates, representatives of groups legally challenging the plant licensing, doctors speaking on the threat of radiation, and indigenous people reminding everyone about the sacredness of the land. Care was taken also not to alienate workers, including preparing special flyers to give to site workers. Richard Grossman and Gail Daneker, who worked with organized labor on energy issues, were guests at the 1976 energy fair.

18 New Hampshire Clam Occupiers…

On August 1, 1976, with some 500 supporters cheering them on, 18 New Hampshire residents walked down the railroad tracks and entered the nuclear construction site. During their non-violence training they’d been encouraged to think of themselves as an “affinity group” for purposes of mutual support. Borrowing from Quaker tradition, decisions by the affinity group were made by consensus, a governance model adopted by the whole Clamshell organization. Consensus decision making aims to ensure that each person’s point of view is heard and everyone’s concerns addressed as fully as possible. It would prove to be an arduous, time-consuming process, but at the same time it created strong bonds among individual Clams as they struggled to craft a group identity and a unified strategy.

During this first occupation, several of the 18 Clams carried tree saplings to attempt a symbolic restoration of the salt marsh, which Public Service Co. had already begun to bulldoze. After extensive but respectful conversations with the police, the 18 Clams ultimately refused orders to leave the site. In the time-honored tradition of civil disobedience, they also chose to go limp when arrested. They were dragged off the site, jailed for the night, and then released pending trial. These 18 and their supporters immediately appealed to other citizens around New England to join them for a second occupation – just three weeks later.

180 New England Clam Occupiers

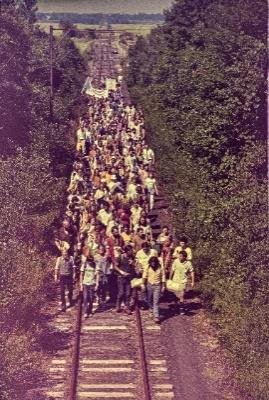

On August 22, 1976, about 1500 people gathered on Hampton Falls Common, just north of Seabrook, for a rally against the Seabrook project. Among them were dozens of Clams from throughout New England who had received training in nonviolent direct action and were organized into affinity groups. While the rally proceeded at Hampton Falls Common, the trained affinity groups followed the railroad tracks onto the site.

The police presence was larger for this second occupation, but the Clamshell strategy was essentially the same. Even as they were being dragged to the school buses used to ferry them to jail, the Clams spoke earnestly to their arresting officers, inviting them to join the movement against nuclear power. After the challenge of talking to a cop who was physically dragging you across hard, rough ground, most Clams found it quite easy to talk about nuclear power with neighbors, co-workers, grocery clerks, toll-booth attendants – virtually anyone they met in the course of daily life.

During a night of detention in the Portsmouth National Guard Armory, the Clam affinity groups did their best to act in solidarity with one another. Some acts of solidarity were quite serious, as when New Hampshire Clams refused to accept release on personal recognizance (no bail required) unless out-of-state Clams also were released without having to pay bail.

Other acts of solidarity were more spontaneous. When it was announced that dinner would consist of hamburgers from McDonald’s, Clams urgently pointed out that some of them were vegetarians and deserved a meal as much as everyone else. Their jailors soon relented, announcing that a vegetarian option would be offered—a sandwich consisting of a bun, lettuce, tomato, pickles, and a “special sauce,” which everyone later agreed tasted exactly like ketchup mixed with mustard.

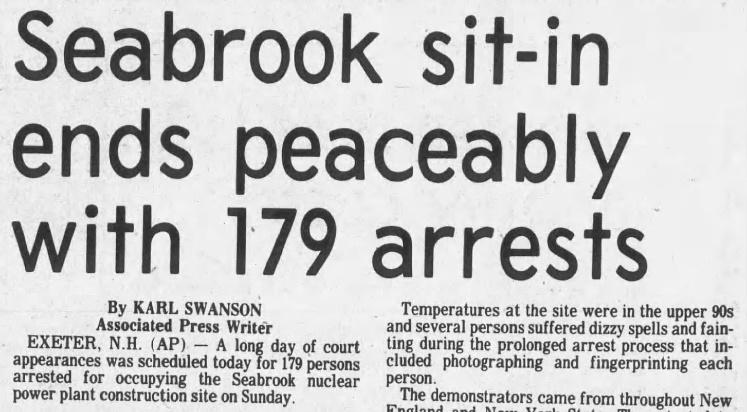

The day after the August 22 occupation, newspapers reported that 179 occupiers from around New England had been arrested at the Seabrook site. On the grapevine, news quickly spread that the police had declined to detain a minor who had participated in the occupation. Some news accounts went with a revised number of 180. With great glee Clam noted that this meant they had succeeded in multiplying their numbers ten-fold.

This remarkable coincidence helped fuel the notion of Clam magic, the idea that magical forces were somehow powering Clamshell’s phenomenal growth. But that growth was just beginning and it wasn’t happening by magic, however much it might feel that way to the participants. It was the result of one-on-one conversations – passionate and relentless – with virtually everyone encountered during this season of belief and hope. If the movement had a “special sauce,” it was more than ketchup and mustard, and more than magic.

It was constant and urgent organizing for the next action.

1,800 Clam Occupiers from 32 States

Despite a sense of urgency, Clams recognized that a national call was needed, especially if the number of occupiers was to grow ten-fold for the next occupation. Recruiting occupiers and training them in nonviolent civil disobedience would take time. Taking a deep collective breath, in the fall of 1976, the Clamshell organized an Alternative Energy Fair instead of an occupation. But a date was set for the next occupation: April 30, 1977.

The fair, at a state park near Seabrook, provided an opportunity to showcase the renewable energy technologies that Clam believed should be pursued instead of nuclear power. The fair, as with all Clam events Guest speakers included Richard Grossman

Also in the fall of 1976, the Clamshell moved into an office in downtown Portsmouth, New Hampshire, about 18 miles from Seabrook. Initially, there was one (minimally) paid staffer – Kristie Conrad – along with several dedicated volunteers. As funds were raised, some of those volunteers also were paid minimally.

The Clamshell Coordinating Committee (CC), made up of representatives of affiliated groups from around New England, met regularly to plan strategy and logistics for the occupation, often sitting for hours in a big circle on the floor (there was very little furniture in the office).

There was only one office rule: answer all the mail every day. An Occupier’s Handbook was created. Several farms (“Friendlies”) were secured where affinity groups could camp the night before the occupation. Routes were laid out and arrangements were made for last-minute training. Plans, although not the locations of Friendlies or exact routes of marches, were shared with state police, as part of Clam’s policy of openness and transparency.

Even with that policy, Gov. Meldrim Thomson Jr., and The Manchester Union-Leader, the state’s largest newspaper, accused the Clamshell of having secret, violent, and possibly Communistic plans. They claimed they had information that there were Clams “ready to die on the site.” They called the occupation the “Red Tide.” (Red tide is an algae bloom that can color sea water and make shellfish toxic.) The Clamshell boosted its credibility by meeting with the governor shortly before the occupation and asking him for any information he might have on people who wanted to cause violence. He offered none.

By March, it appeared there would be people coming from at least 32 states, including a street theater group from DeKalb, Illinois, a group from the War Resisters League in New York City, and Movement for a New Society out of Philadelphia.

The morning of April 30, 1977, was sunny and clear. About 1,800 (yes, Clam magic) occupiers, singing and carrying banners, approached the site from four directions, including a large group from the east, through the marshes. Although police from three states were present, they did not block entry. Occupiers walked onto the dusty construction site parking lot and sat down, expecting to be arrested. Nothing happened so they began to set up their tents, dig latrines, prepare meals, and, of course, hold meetings. They also found ample time to hug, dance, and sing in celebration. By the time arrests started the following day, hundreds of occupiers had returned to their jobs or other obligations. But 1,415 had remained on the site and were arrested.

The arrested were sent to five National Guard armories and several county jails, where they settled in. They continued protesting – preventing separation of men and women in one armory, blocking guards from taking people to arraignments in another. There was singing, drumming, dancing, fashion shows, talent shows, sharing food (all occupiers came with food in their backpacks), and workshops galore. And there were a lot of earnest conversations with guards about nuclear power. While about half of the detainees had to bail out or accept personal recognizance early, there were still more than 500 locked in the armories 13 days later when the state finally let everyone go – without bail.

The 1977 occupation and subsequent incarceration were widely reported, sparking creation of similar direct action, anti-nuclear power alliances across the country, including Abalone, Shad, Crabshell, Trojan Decommissioning, Lone Star, Palmetto, Sunflower, and Paddlewheel alliances.

And the Clamshell started organizing for a June 24, 1978 occupation, determined to bring 18,000 trained occupiers to Seabrook.

Not Quite an Occupation

But Clam magic was coming up against obstacles – externally as well as internally.

Externally, construction was underway and tall fences had been erected around the site. In addition, the Clamshell began to realize its culture of transparency made it vulnerable to infiltration by the state and PSCo. In fact, it was learned in the spring of 1978 that PSCo was tapping the home phones of some Clam activists and that state police were taking photos of people attending Coordinating Committee meetings.

Internally, there were other issues.

Quaker-inspired consensus decision-making had helped create a strong, unified, non-hierarchical, and open Clamshell – at least when there was clear agreement on fundamental goals and tactics. As the number of people interested in helping plan and participate in the next occupation grew, some goals — and even more, some tactics — became points of division.

The deepest divisions developed around the issue of whether or not fences should be cut to gain access to the site. Cutting fences challenged the informal rule of no property damage, a tenet designed to avoid unnecessary provocation of police, promote a nonviolent atmosphere, and maintain the support of local residents. Proponents of breaching the fences argued that access to the site was necessary for a serious occupation – an action they hoped could have the same success as a citizen occupation that stopped construction of a nuclear power plant in Wyhl, Germany, in 1975. The committee charged with organizing the occupation developed a proposal to allow groups that chose to breach the fences to do so. But others objected to the idea of so radically mixing occupation tactics.

In the middle of this debate, New Hampshire Atty. Gen. Tom Rath made an end-run that led to a drastic change in plans. Just weeks before the occupation, Rath convinced the governor and his Executive Council to offer the Clamshell a lawful rally on the site, instead of an occupation. It was learned later that Rath timed the offer because he knew of the Clam’s internal divisions and its time-consuming decision-making process.

The Coordinating Committee (CC) tried to figure out how to respond to the Rath proposal. People from the Clam office traveled to other parts of New England to share information and gather feedback, which included strong support for going ahead with the occupation. The Clam finally offered to accept the proposal if the state met a list of conditions including “immediate end to construction.” The list was perceived – by the state and media – as a rejection of the offer. Plans for the occupation continued.

At the same time, some residents near the site, including several who had offered staging grounds (“friendlies”) for occupiers, began withdrawing their support. They said they feared violence on their properties – from the police, the occupiers, or both.

The Clamshell always had relied on local support. Key to that support was good organization, and the assurance that people who participated in occupations were trained in nonviolence and would be orderly. With thousands of occupiers expected from as far away as Vancouver, Canada, there was concern that there might be chaos without secure staging grounds for the occupation.

Long, intense meetings of the CC continued. That group finally made an emergency decision – accept the Rath proposal, even if the Clamshell’s list of conditions was not met, and move ahead with a lawful rally on the site.

It was an emergency decision because the CC decided there wasn’t enough time to seek consensus from all New England groups, as well as a fear, even with adequate time, that no consensus could be reached.

According to The New York Times, 20,000 people were there, including pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock and nuclear physicist John Gofman. Rally performers included Pete Seeger, Jackson Browne, Arlo Guthrie, and comedian-activist Dick Gregory.

Meanwhile, over in Concord, New Hampshire, that same day, the governor hosted a pro-nuclear rally and clambake. About 1,000 people attended.

Not wanting to abandon civil disobedience altogether, plans also were made for a different sort of occupation a few days following the Seabrook rally. People would travel to Washington D.C. and occupy the street in front of the offices of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which, coincidentally, was considering a challenge to the Seabrook nuke’s proposed cooling system. It was an energized protest, but the numbers were in the hundreds instead of the hoped-for thousands.

Post-1978 Seabrook Protests

Calling off the occupation and bypassing consensus decision-making deflated faith in the Clamshell Alliance – externally as well as internally. The Clam, moved its office to Concord and continued, with smaller numbers and actions, to fight the nuke well into the 1980s, including encouraging a series of small “wave” actions of civil disobedience and protest at the site, usually involving 10 to 20 people. The Clam also targeted the state’s Public Utilities Commission and Seabrook investors, including the Bank of Boston. But it never regained the numbers or credibility it had in 1977. Whether or not calling off the occupation was the right decision, made the right way, continued to be debated passionately by some Clams for decades.

In March 1979, there was a Clamshell action attempting to block delivery to the site of the reactor core, with hundreds of people lining the roads of Seabrook and 170 arrests. Later that year, more than 1,045 anti-nuclear activists were arrested when they blocked entrance to the New York Stock Exchange on the 50th anniversary of the Great Crash. The action was organized by a coalition of 100 anti-nuclear organizations from around the nation. It was not “owned” by the Clamshell, although some Clams, along with a couple of New York City organizations, played a central role. In fact, the idea originated with Renny Cushing, a founding Clam, and Clams produced the action’s handbooks.

People most disappointed with the emergency decision to accept the Rath proposal formed a new group – Coalition for Direct Action at Seabrook (CDAS)—and organized an October, 1979 occupation. About 2,000 occupiers from across the country pulled down fences and entered the site. They were dispersed by police with tear gas, batons, and fire hoses. CDAS mounted a similar action in 1980, but attracted fewer people.

There was a revival of direct-action protests in the wake of the 1986 Chernobyl accident, and in 1989, as the Seabrook Station sought an operating license, more than 1,000 Clams used ladders to go over the fences onto the Seabrook site. Other anti-Seabrook nuke actions post-1978 included the toppling of a siren tower by Guy Chichester and a legal rally where scores of people wore buttons that read, “Clam Leader,” after the state tried to prosecute five Clams as “leaders.”

The Clamshell Alliance built a model – transparency, nonviolence training, affinity groups, and the use of consensus decision-making – that was adopted not only by similar anti-nuclear groups, but by also by other organizations seeking social change.

Many of the individuals most active in the Clam continued to speak, write, teach, and organize around energy issues throughout the country. For instance, Harvey Wasserman and Sam Lovejoy, longtime Clams, helped create Musicians United for Safe Energy (MUSE), which staged a series of anti-nuclear fund-raising concerts in Madison Square Garden and an outdoor rally/concert – attended by 200,000 people — the week before the Wall Street Action sit-in in 1979. Paul Gunter, also a longtime Clam, co-founded Beyond Nuclear, which continues to advocate against nukes and for safe energy. And those are only two of dozens.

And Then?

A Clamshell founder, Granite State Alliance director Jeff Brummer, worked hard to make the financing of the Seabrook nuke construction the chief issue of the 1978 governor’s election in New Hampshire. Construction Work in Progress (CWIP) allowed the utility to put the cost of building the plant into its rate base long before it produced any electricity. Largely because of the CWIP issue, Democrat Hugh Gallen defeated Gov. Meldrim Thomson and, as governor, immediately drafted a successful anti-CWIP bill.

The Public Service Company of New Hampshire, as anti-nuclear activists had predicted, crumpled under the weight of the nuke’s massive costs and the death of CWIP. It declared bankruptcy in 1987, the first electric utility to do so since the Great Depression. Seabrook Unit two was cancelled with a sunk construction cost of $900 million. New owners were found and the other Seabrook reactor finally went into commercial operation in August, 1990, 11 years behind schedule. It cost $6.2 billion, more than six times the original price tag, and has generated some of the most expensive electricity produced in the U.S.

For more than 30 years after that, no new nuclear power plant construction licenses were sought or issued. Then in 2005, the government passed new legislation that again made things easier for commercial nukes, with hopes of sparking a nuclear renaissance. But the results were dismal, resulting in only two new reactors, Vogtle Units 3 and 4 in Georgia.

The government and the industry are at it again – flooding us with propaganda, including social media campaigns, insisting that nukes are essential for dealing with climate change, and that the nuclear industry should receive huge federal subsidies.

It’s time again to speak truth to power — loudly. That’s what the Clamshell Alliance did in the 1970s. And it made a difference.